Can a brain injury change who you are?

![]() This article by , PhD researcher in Neuropsychology at the School of Psychology was originally published on . Read the .

This article by , PhD researcher in Neuropsychology at the School of Psychology was originally published on . Read the .

Who we are, and what makes us “us” has been the topic of much debate throughout history. At the , the ingredients for the unique essence of a person consist mostly of personality concepts. Things like kindness, warmth, hostility and selfishness. Deeper than this, however, is how we react to the world around us, respond socially, our moral reasoning, and ability to manage emotions and behaviours.

Philosophers, including Plato and Descartes, attributed these experiences to non-physical entities, quite separate to the brain. “”, they describe, are where human experiences take place. According to this belief, souls house our personalities, and enable moral reasoning to occur. This idea still enjoys substantial support today. Many are comforted by the thought that the soul does not need the brain, and mental life can continue after death.

If who we are is attributed to a non-physical substance independent of the brain, then physical damage to this organ should not change a person. But there is an overwhelming amount of neuropsychological evidence to suggest that this is, in fact, not only possible, but relatively common.

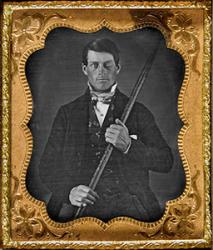

Phineas Gage, after injury. : Originally from the collection of Jack and Beverly Wilgus, and now in the Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical School.The perfect place to start explaining this is the curious case of .

Phineas Gage, after injury. : Originally from the collection of Jack and Beverly Wilgus, and now in the Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical School.The perfect place to start explaining this is the curious case of .

In 1848, 25-year-old Gage was working as a construction foreman for a railroad company. During the works, explosives were required to blast away rock. This intricate procedure involved explosive powder and a tamping iron rod. In a moment of distraction, Gage detonated the powder and the charge went off, sending the rod through his left cheek. It pierced his skull, and travelled through the front of his brain, exiting the top of his head at high speed. have since revealed that the likely site of damage was to parts of his prefrontal cortex.

Gage was thrown to the floor, stunned, but conscious. His body eventually recovered well, but Gage’s behavioural changes were extraordinary. Previously a well-mannered, respectable, smart business man, Gage reportedly became irresponsible, rude and aggressive. He was careless and unable to make good decisions. Women were advised not to stay long in his company, and his friends barely recognised him.

A similar case was that of photographer and forerunner of motion pictures . In 1860, Muybridge was involved in a stagecoach accident and sustained a brain injury to the (part of the prefrontal cortex). He had no recollection of the crash, and developed traits that were quite unlike his former self. He became aggressive, emotionally unstable, impulsive and possessive. In 1874, upon discovering his wife’s infidelity, he shot and killed the man involved. His attorney pled insanity, due to the extent of the personality changes following the accident. Sworn testimonies emphasised that “he seemed like a different man”.

Perhaps an even more is that of a 40-year-old school teacher who, in the year 2000, developed a strong interest in pornography, particularly child pornography. The patient went to great lengths to conceal this interest, which he acknowledged was unacceptable. But unable to refrain from his urges, he continued to act on his sexual impulses. When he began making sexual advances towards his young stepdaughter, he was legally removed from the home and diagnosed with paedophilia. Later, it was discovered that he had a brain tumour displacing part of his orbitofrontal cortex, disrupting its function. The symptoms resolved with the removal of the tumour.

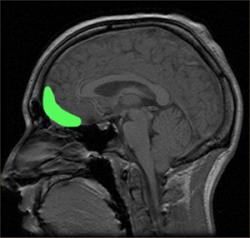

MRI scan showing approximate location of the orbitofrontal cortex. : Wikimedia/Paul WicksDifferent personalities

MRI scan showing approximate location of the orbitofrontal cortex. : Wikimedia/Paul WicksDifferent personalities

All these cases have one thing in common: damage to areas of the , in particular the orbitofrontal cortex. Although they may be extreme examples, the idea that damage to these parts of the brain results in severe personality changes is now . The prefrontal cortex has a role in , and responding appropriately. So it makes sense that disinhibited and inappropriate behaviour, psychopathy, , and impulsivity have all been linked to damage of this area.

However, changes after injury can be more subtle than those previously described. Consider the case of , who suffered a severe traumatic brain injury after falling off a roof while supervising a building construction. His later aggressive behaviour and delusional jealousy about his wife’s apparent infidelity caused a breakdown in their relationship. To her, he was not the same man anymore.

Difficulties with emotion management like this are not only distressing, but are predictive of , negative social changes and greater . Many brain injury survivors also suffer with and , while struggling to adjust to post-injury life.

But with a growing appreciation of the relevance of emotional adjustment in rehabilitation, have been developed to help manage these changes. In our lab, we have developed the BISEP (Brain Injury Solutions and Emotions Programme), which is a cost-effective, education-based, group therapy. This addresses several common complaints of brain injury survivors and has a strong emphasis on emotion regulation. It teaches attendees strategies that can be used adaptively and independently, to help manage their emotions and associated behaviours. Although it is early days, we have obtained some positive preliminary results.

From a neuropsychological perspective, it’s clear that who we are is dependent on the brain, and not the soul. Damage to the prefrontal cortex can change who we are, and though people have become unrecognisable from it in the past, new strategies will make a big difference to their lives. It may be too late for Gage, Muybridge and others, but brain injury survivors of the future will have the help they need to go back to living their lives as they did before.

Publication date: 20 April 2018